Competencies

When he was in town last week Patrick pointed us to an article in the Economist discussing Obama's Social Innovation Fund which launched this summer. Although small money from the perspective of the US government, 50 million USD is a substantial vote of confidence for the social innovation community. The Obama initiative is aimed at ramping up existing projects, a necessary tool as members of the SI community attempt to prove the viability of their methods at scale.

Obama's fund has a lot of potential to enable groups delivering new efficiencies in situations where a problem is known but not well solved. Solution X, a better alternative comes along, so let's find a way to make sure Solution X has the capital it needs to get started. This includes privatization with an emphasis on competition and new social ventures positioned between the market and 3rd sectors, in effect augmenting both (think microfinance or the Omidyar Network).

But what about those situations where the problem itself is unclear? This is the context of systemic failures—all parts might be functioning very well, but they're not sufficiently coordinated as a group. The glue is missing, and maybe some key parts too. The American healthcare system (if it could be called that) is a prime example of this.

To create strategic impact in these areas there are three critical dimensions which need to be addressed.

- Team: problems that exist at the intersection of multiple areas of interest always require teams of multiple expertise.

- Money: good will only lasts so long.

- Legal and regulatory support: Stephen Goldsmith, now chairman of the group that oversees the Social Innovation Fund, hit the nail on the head: “I can think of 1,000 innovations. I have not yet had an innovative idea in any meeting that was legal.”

To work on those kinds of problems a different approach is needed because they are 'pre-market.'

This is kind of thing that our brains are churning on these days.

What are architects good at? What roles might a background in architecture prepare an individual for? These are some of the questions that Martti Kalliala and Hans Park set out to answer in their New Architect's Atlas, part of a publication called Double Happy (8+8=19) – Views on Architecture in Finland and China which our friends over at OK Do recently put together. In their own words:

The near-collapse of our financial system has had tremendous effects on the architectural profession. The number of unemployed architects worldwide is higher than ever before. This, combined with the fragmentation of the building process into the hands of specialist consultants and the shift from architects being in the service of public to private capital, has made a lot of the work and responsibilities that traditionally belonged to them simply disappear or move to other professional domains. This is why newly graduated architects have difficulties finding jobs that match their education, creative ability or ambition – not to mention the thousands of students facing an increasingly uncertain future.

All images courtesy of Martti Kalliala and Hans Park.

As communicator of material implications of decisions...

As maker of spaces, both cultural and physical...

As resource for civil society...

As link within broader building and city delivery ecosystem...

See the full post here.

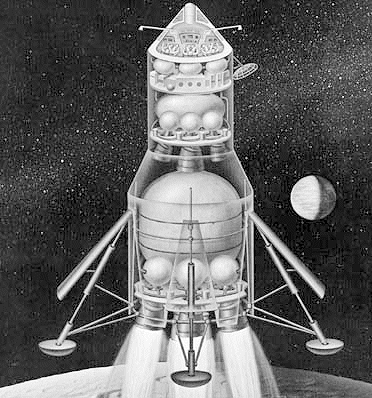

Announcing a new approach to space exploration yesterday, President Obama shifted the focus from getting somewhere to building capability.

“Step by step, we will push the boundaries not only of where we can go but what we can do... In short, 50 years after the creation of NASA, our goal is no longer just a destination to reach. Our goal is the capacity for people to work and learn, operate and live safely beyond the Earth for extended periods of time.”

-President Obama in the New York Times

The Apollo project of the 1960s mobilized a massive amount of money, people, and effort to put a man on the moon. In the eight years between President Kennedy's announcement that the US would shoot for the moon and Neil Armstrong's first steps on lunar soil, NASA answered questions no one had ever asked before.

To be simplistic, there's no such thing as a single challenge. Challenges come in bundles. The difficulty is that it's very hard to predict in advance the nature of the bundle and to define the boundaries of the challenge. One may aspire to go to the moon but would they expect, from the outset, to research food enrichment as a step to getting there?

The sheer size of the Apollo project's ambition required the people involved to invent solutions to seemingly unrelated problems. The results of this are important to our everyday lives in ways that most people (including me) don't acknowledge, probably don't even know about. From enriched baby food to computer controlled fabrication (CNC), the secondary benefits of the space program are many, even if their pace has slowed.

Source: Wikipedia

NASA's leadership of the space effort was a success in the 20th century when the target was difficult yet clear defined. One could argue that the success of the moon mission was derived from an institutional ability to pursue the right answer.

Nowadays we increasingly encounter problems that are ill-defined (or fuzzy or wicked, take your pick) and the question, as such, might not even exist yet. Today success still relies on choosing the right answer, as it always will, but we also have to ask the right questions.

This requires a shift of focus from building institutional capability towards building a culture of capability. Setting a new target, like Mars, may be dramatic, but it's not responsive to the ways that our context has changed in the past 40 years. We know the headlines (climate change, health care, etc) but the actual boundaries of these challenges need to be continually developed. To do this we need a culture that understands problems and solutions as moving targets, constantly in development together. HDL sees strategic design as one of the steps towards building this culture.

Neil Armstrong tacitly acknowledged the diminishing returns of a business-as-usual space program by noting that, "[going to Mars] will be expensive [and] it will take a lot of energy and a complex spacecraft. But I suspect that even though the various questions are difficult and many, they are not as difficult and many as those we faced when we started the Apollo (space program) in 1961." In other words, we know the boundaries of that problem pretty well and the development of new knowledge will be now incremental rather than stepwise.

The sheer complexity of working in space makes it a crucible of innovation, but unless we're asking the right questions and setting the right targets–unless we continue to define the boundaries of the challenge–the returns will continue to diminish.

For Mr. Kennedy it was enough to go to the moon because "it is there" and those were heady days. To deliver on Mr. Obama's intentions of an expanded capability to work and live in space we'll have to first figure out what it is we want to do. That sounds like a mighty design brief to me.

Over at frog design they've been talking about what it is that designers do, and have proposed a rather interesting pivot for the conversation: magic. As they tell it the world has two kinds of designers, those who are pro-magic and those who are not.

In the first camp: “What we do has nothing to do with magic! We design objects and interactions for people, in the clearest and most logical way... We help people survive in the world.” In other words, design is about function, purpose, usability.In the second camp: “Of COURSE what we do is magic! We are nothing if not magicians, making the impossible real, bringing the just-out-of-reach right into the palms of our hands. Whether objects, or experiences, we create the moment of wonder and delight.” In other words, design is about meaning, emotion, even transcendence, if you will.

This sharp distinction seems a little overzealous, though. Like many things, the answer is somewhere in between. Design practiced well should always have a purpose and function, and to do that it must often "[make] the impossible real." The fact that designers work from conception to implementation is a unique professional obligation and involves the resolution of conflicts and impossibilities of all sorts into a seamless and singular material reality. That itself is a kind of magic.

To actually produce an object or service the designer must rectify conflicting client desires, material behaviors, economic envelopes, and numerous other requirements. This is the really hard part. If the designer is successful, these disparate inputs are dissolved into a wash of intention – as if by magic – and the resultant thing just works in ways equally delightful and useful.

The difficulty of implementation is one of the reasons why "design thinking" is not enough. Putting aside for now a lengthy but necessary discussion about rebooting the practice of design and the way we educate our designers, "design thinking" is only half of the value proposition. A design proposal, no matter how insightful, clever, and well researched is only ever a mere tiptoe into the journey. The success of good design is always the result of combined thinking and doing.

Try out any of the numerous iPhone lookalikes to understand the importance of a continuous spectrum from idea to final product. Even with the same feature set, aesthetics, and ambitions, every iClone I've tried pales in comparison to the original. If there's magic in design it's the practical magic of making any friction between abstract possibilities (ideas!) and material reality (things!) disappear. This, finally, is design thinking and design stewardship working in conjunction to deliver work of the highest caliber.

Interviewed in the Architect's Newspaper yesterday, celebrated British architect David Adjaye responds candidly to some very direct questions about the financial troubles that his practice has faced, and is now recovering from. This is worth pointing out for two reasons.

It's great that he's willing to admit that things were difficult! So often in the design professions we do everything we can to keep a clean portfolio, a straight face, and an air of effortless accomplishment. But practitioners do fall down, they do make mistakes, and they do occasionally suffer because of it. The question is how you learn and recover from those challenges (and sometimes failures too). The more designers are actively sharing their experiences of both success and failure, the more we can collectively figure out ways to gracefully overcome challenges.

Secondly, it's great to see Adjaye reflecting on his own experience setting up his practice as a studio and a business. The world has changed a lot since the studio model of design education was developed in the 19th century: what should we do to bridge that gap? I'll let Adjaye address this question:

Schools are woefully unconnected to the idea of the profession being entrepreneurial. We were all graduating and trying to get into employment right away. This generation is very different, because they’re paying off their debts. In my day in London, it was still very much in the grant system. Your education wasn’t a noose around your neck in terms of repayment. It was almost like free, and you were very ready to take on the world and come into the world. There was more risk-taking.