As I write this, my mind is a few days in the future, thinking about Friday at 9:30 when we will kick off "official" HDL 2012 activities. That's a rather serious-sounding way of saying that Justin and I will spend a day with six smart people in a nice room. Where HDL 2010 was about distilling a grand challenge into an actionable strategic intent, Helsinki Design Lab Global 2012 is…

about stewardship; or in other words, how innovative things get done. With the global conversation increasingly invoking the (re)design of systems, institutions, markets, and even the social contract, HDL 2012 is an opportunity to reflect upon the necessary innovation required of innovation itself. How do we shape policy through projects? How do we connect strategy to execution? How do ‘clients’ of innovation maximise their value and agency?

New practices, new themes, and even new vocabularies emerge as this community grows. Helsinki Design Lab 2012 is an opportunity to take stock of these emerging practices and begin to codify new ways of doing.

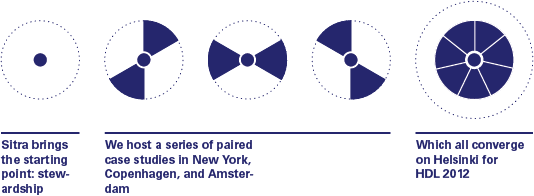

When we wrote the first three HDL case studies back in 2009-2010 we did so because the best innovators in the world rarely have the time to step back from their work and codify it in ways that others can make use of. And understandably, it takes time to reflect and then package those reflections, and that's time which can be used doing more good work! So beginning with those cases and now continuing with what we expect to be six more cases between now and October, we are using HDL 2012 to gain a deeper understanding of how innovation is accomplished by different cultures of decision making.

It's a comparative study of innovation practice, really. We've invited two public bodies, two NGOs, and two private entities to contribute one project each. Together these six practices span Europe, North America, and South America, and they work in areas ranging from community planning to business oversight.

Summer in Åland, the archipelago between Sweden and Finland

The sheer diversity of the group was one of the things we were equivocal about for some time. A typical comparative study might seek to minimize the variables to down one—a range of public, private, and third sector organizations all addressing homelessness, for instance, and all in the same geography. But this year we will be juggling multiple variables that change from case to case, and the reason is rather straightforward: we have tried to recruit from the best of the best in public innovation, and that means accepting a more diverse set of projects. It would be crazy to assume that the best of contemporary practices are captured within any single field.

We're also experimenting a bit with the format. Rather than Sitra conducting one-on-one case studies, we're bringing together two cases at a time and asking the teams to help us interview and analyze their counterparts. This means that we'll have extra brain power in the room to ask the right questions and evoke the right discussion. Our hypothesis is that having practitioners interview practitioners will help us keep our heads out of the clouds. Someone who has been-there-done-that has a unique ability to stop things and ask questions like OK, but how did you really pull that off?

The kind folks at Monitor Group + Doblin have graciously loaned us one of their conference rooms (thanks especially to Helen Walters!) where we will spend the half the day discussing the reconstruction of Constitución, Chile after the 2010 earthquake and tsunami and half the day focusing on the revitalization of Brownsville, NY. Alejandro Aravena and Rodrigo Araya will be sharing their experience with the work in Chile and Rosanne Haggerty will be joined by a number of people from her team on The Brownsville Partnership. We're lucky to have been following their work for a while, and personally I'm looking forward to getting a good chunk of time to understand their recent efforts in depth.

Friday will be the first of three case sessions leading up to a culminating event in Helsinki in mid-October. It's going to be a small affair with only about forty people, but as always we will do our best to make sure that the learnings are shared as widely as possible.

Outside of the intensifying work on HDL 2012, I've been hosting the occasional group for a talk at Sitra (thanks for coming, EGOS) and working on some back burner projects (more on those in a second). Kalle is in the office tending to our food work which now has the beginnings of a web presence. Marco, Dan, Justin, and Maija are enjoying various depths of the summer holiday.

Clear evidence that Marco has been in the office, and so have his kids.

The renovation project we've been working on in the office continues to inch forward. I'm looking forward to this being done.

At the risk of making us sound obsessed with codification, I've been taking advantage of the slow pace of the office in summer to revive a long overlooked "manual for creative collaboration." We had the opportunity a couple years ago (!!!) to commission the Open-Ended Group to write a pamphlet on how to get the most out of collaborative work, but we've been so busy with everything else that it's only now that I've found the time to open those files again. It's good, simple, clear text and I've allowed myself the indulgence of devoting time to experiment a bit with the layout, taking inspiration from the lovely Bauhaus typography I saw at the Barbican in London recently. Eventually this will sit alongside the Design Ethnography field guide as a small practical manual.

Draft layouts of the collaboration booklet.

After spending two extremely intense days in Copenhagen with a group of people running various "design labs" at the beginning of the month, I'm once again struck by how much shared territory there is in the various approaches, and yet such significant differences in the way that different groups describe their work. That these practices are being cobbled together from a combination of social science, design, media, entrepreneurship, public administration, and other backgrounds means that a common ground doesn't come naturally but must be willfully created. The lack of shared vocabulary makes the true overlaps harder to see and positive differences harder to highlight.

Take "participation," for instance. Different groups use the term "participation" variously to mean working with people to create novel ideas, conduct due diligence on proposals, or secure wider buy-in for a course of action—and sometimes a combination of these. But those are three very different ways to use "a bunch of people in a room doing something together," each with their own nuances, pitfalls, and benefits. No wonder Markus Miessen refers to the Nightmare of Participation!

Thanks to Banny Banerjee, Christian Bason, Tim Brodhead, Luigi Ferrara, Sam Laban, Cheryl Rose, Frances Westley for the generous discussion. There will be a summary paper coming from that meeting which we'll post here when it's available.

Banny explaining the Stanford d.School design process.

There's a CNC fabrication shop in that basement. Copenhagen knows how to make a courtyard.

That you can buy mini turbines at a toy shop in Copenhagen says a lot about deeply renewable energy has soaked into Danish culture.

For a final and more entertaining note on collaboration, codification, and getting things done, I leave you with this video introduction for new employees of New York-based artist Tom Sachs' studio.